Реферат: Teddy Roosevelt

Реферат: Teddy Roosevelt

Report

Theodore Roosevelt

Icon of the American Century

“The joy of living is his who has the heart to demand it.”

Theodore Roosevelt

executed: Magomedova Z.A.

examined: Akhmedova Z.G.

Makhachkala 2001

Contents - Introduction

page

3 - Maverick in the Making , 1882 – 1901

page 3 -

Rough Rider in the White House , 1901 – 1909

page 7 - The Restless

Hunter , 1909 – 1919

page 10 -

Chronology of the Public Career of Theodore Roosevelt

page 14 - Source

page

15

Introduction

The life of Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) was one of constant activity, immense

energy, and enduring accomplishments. As the twenty-sixth President of the

United States, Roosevelt was the wielder of the Big Stick, the builder of the

Panama Canal, an avid conservationist,

and the nemesis of the corporate trusts that threatened to monopolize American

business at the start of the century. His exploits as a Rough Rider in the

Spanish-American War and as a cowboy in the Dakota Territory were indicative of

his spirit of adventure and love of the outdoors. Reading and hunting were

lifelong passions of his; writing was a lifelong compulsion. Roosevelt wrote

more than three dozen books on topics as different as naval history and African

big game. Whatever his interest, he pursued it with extraordinary zeal. "I

always believe in going hard at everything," he preached time and again. This

was the basis for living what he called the "strenuous life," and he exhorted

it for both the individual and the nation.

Roosevelt's engaging personality enhanced his popularity. Aided by scores of

photographers, cartoonists, and portrait artists, his features became symbols

of national recognition; mail addressed only with drawings of teeth and

spectacles arrived at the White House without delay. TR continued to be

newsworthy in retirement, especially during the historic Bull Moose campaign

of 1912, while pursuing an elusive third presidential term. He remains

relevant today. This exhibition is a retrospective look at the man and his

portraiture, whose progressive ideas about social justice, representative

democracy, and America's role as a world leader have significantly shaped our

national character.

Maverick in the Making , 1882 - 1901

Theodore Roosevelt was born on October 27, 1858, in a brownstone house on

Twentieth Street in New York City. A re-creation of the original dwelling,

now operated by the National Park Service, replicates the tranquility of

Roosevelt's earliest years. His father, Theodore Roosevelt Sr., was a

prosperous glassware merchant, and was one of the wealthy old Knickerbocker

class, whose Dutch ancestors had been living on Manhattan Island since the

1640s. His mother, Martha Bulloch, was reputedly one of the loveliest girls

to have been born in antebellum Georgia. Together the parents instilled in

their eldest son a strong sense of family loyalty and civic duty, values that

Roosevelt would himself practice, and would preach from the bully pulpit all

of his adult life.

Unfortunately the affluence to which the young Theodore grew accustomed could

do little to improve the state of his fragile health. He was a sickly,

underweight child, hindered by poor eyesight. Far worse, however, were the

life threatening attacks of asthma he had to endure until early adulthood. To

strengthen his constitution, he lifted dumbbells and exercised in a room of

the house converted into a gymnasium. He took boxing lessons to defend

himself and to test his competitive spirit. From an early age he never lacked

energy or the will to improve himself physically and mentally. He was a

voracious reader and writer; his childhood diaries reveal much about his

interests and the quality of his expanding mind. Natural science,

ornithology, and hunting were early hobbies of his, which became lifelong.

In the fall of 1876, Roosevelt entered Harvard University. By the time he

graduated magna cum laude, he was engaged to be married to a beautiful young

lady named Alice Lee. The wedding took place on Roosevelt's twenty-second

birthday. Amid the intense happiness he experienced during his first year of

marriage, he laid the foundations of his historic public career. "I rose like a

rocket," he said years later. Ironically, when he chartered his own path for

public office--the White House in 1912--he failed bitterly. When others had

selected him--as they did for the New York Assembly in 1881, for the

governorship in 1898, and for the vice presidency in 1900--his election was

almost a foregone conclusion. Politics aside, Roosevelt shaped and molded his

life as much as any person could possibly do. He could not control fate,

however. On Valentine's Day, 1884, his mother died of typhoid fever and his

wife died of Bright's disease, two days after giving birth to a daughter, Alice

Lee. Amidst this personal trauma, Theodore Roosevelt was on the verge of

becoming a national presence.

Between 1882 and 1884, Theodore Roosevelt represented the Twenty-first

District of New York in the state legislative assembly in Albany. An 1881

campaign broadside noted that the young Republican candidate was "conspicuous

for his honesty and integrity," qualities not taken for granted in a city run

by self-serving machine politicians. This was the start of Roosevelt's long

career as a political reformer.

Roosevelt's political alliance with Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts

began in 1884, when the two were delegates to the Republican National

Convention in Chicago. In time, both men would become leaders of the Republican

Party. Their extensive mutual correspondence is an insightful record of shared

interests and American idealism at the turn of the twentieth century. After

serving in the United States House of Representatives for six years, Lodge

became a senator in 1893 and retained his seat for the rest of his life. Like

Roosevelt, Lodge was an advocate of civil service reform (he recommended

Roosevelt to be a commissioner in 1889), a strong navy, the Panama Canal, and

pure food and drug legislation. A specialist in foreign affairs, Lodge acted as

one of Roosevelt's principal advisers during his presidency. Yet Lodge did not

support many of Roosevelt's progressive reforms—women's suffrage, for

instance—and he refused to endorse his friend in the Bull Moose campaign of

1912.

Love of adventure and the great outdoors, especially in the West, were the bonds

that sealed the friendship between Theodore Roosevelt and Frederic Remington.

"I wish I were with you out among the sage brush, the great brittle

cottonwoods, and the sharply-channeled barren buttes," Roosevelt wrote to the

western artist in 1897 from Washington. After the death of his wife Alice Lee

in 1884, Roosevelt moved temporarily to the Bad Lands in the Dakota Territory,

where he owned two cattle ranches. In 1888, Century Magazine

published a series of articles about the West written by Roosevelt and

illustrated by Remington. In a May article, Roosevelt told the story of his

daring capture of three thieves who had stolen a boat from his Elkhorn Ranch.

Remington depicted their capture in this painting.

Jacob Riis was a valuable friend and source of information for Roosevelt

when he became a New York City police commissioner in the spring of 1895. As a

police reporter for the New York Evening Sun, Riis understood the

reforms needed within the police department, as well as the evils in the slums,

which he frequented to gather stories. Riis was successful in awakening public

awareness to the plight of New York's tenement population, especially the

children, in several books, including his classic How the Other Half

Lives. In 1904 Riis published a biography of his good friend, with whom

he used to walk the streets of New York, titled Theodore Roosevelt: The

Citizen.

I have I have

"developed a playmate in the shape of Dr. Wood of the Army, an Apache

campaigner and graduate of Harvard, two years later than my class," Roosevelt

wrote from Washington in 1897. "Last Sunday he fairly walked me down in the

course of a scramble home from Cabin John Bridge down the other side of the

Potomac over the cliffs." Theodore Roosevelt and Leonard Wood liked

each other from their first meeting that spring. Both were robust and athletic,

and both, from the vantage points of their respective jobs—Roosevelt as

assistant secretary of the navy, and Wood as an army officer (and the physician

of President and Mrs. William McKinley)—took a belligerent attitude toward

Spain with respect to Cuba. When Roosevelt was offered the chance to raise a

regiment of volunteer cavalry, he in turn recruited the more experienced Wood

to be the regiment's colonel and commander. After the war in Cuba, Wood

remained as military governor of Santiago, and shortly thereafter was appointed

to administer to the affairs of the entire island.

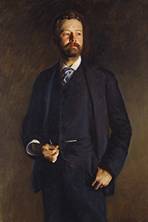

John Singer Sargent painted this portrait of Wood in 1903, when he went to

Washington to do the official portrait of President Roosevelt. Sargent

recalled then that the two veteran Rough Riders enjoyed competing against

each other with fencing foils.

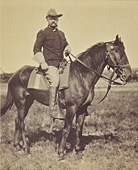

After his return from the war in Cuba, Colonel Roosevelt posed for this

photograph at Montauk, Long Island, shortly before his First Volunteer Cavalry

Regiment was mustered out of service in September 1898. Later, in a letter to

sculptor James E. Kelly—who like Frederick MacMonnies sculpted a statuette of

the Rough Rider upon a horse—Roosevelt described in detail how he looked and

dressed in the war. Unlike his image here, he said, "In Cuba I did not have the

side of my hat turned up."

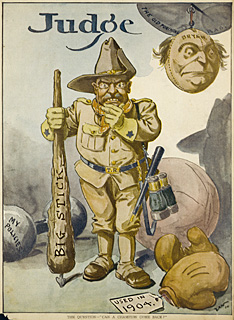

Theodore Roosevelt emerged from the Spanish-American War a national hero. His

military fame now enhanced his reputation as a reform politician in his home

state of New York, where he was nominated to run for the governorship that

fall of 1898.

This cartoon appeared in Judge, October 29, 1898, just prior to

Roosevelt's successful election, and predicted his ultimate political destiny,

the White House.

President William McKinley represented the status quo for most Americans

at the turn of the century. By and large, they were comfortable with him in the

White House. As the standard bearer of the Republican Party, he was an

unassuming bulwark of conservatism. He stood for the gold standard, for

protective tariffs, and of course for a strong national defense during the

Spanish-American War. McKinley's personal attributes were affability and

constancy, not dynamism and originality. Politically he was a follower and not

a reformer, like Roosevelt. If the idea of having TR on the ticket as Vice

President seemed at odds with the President's relaxed style, it was perfectly

like Mckinley to go along with what the party and the people wanted. He never

admitted to sharing the fears of his good friend and political advisor, Ohio

Senator Marcus Hanna, who was also chairman of the national Republican

committee. For Hanna, Roosevelt was too young, too inexperienced and too much

of a maverick. He could not help but think: What if McKinley should die in

office?

Rough Rider in the White House , 1901 - 1909

No event had a more profound effect on Theodore Roosevelt's political career

than  the assassination of the assassination of

President William McKinley in September 1901. At the age of forty-two, Vice

President Theodore Roosevelt took the oath of office, becoming the youngest

President of the United States before or since. From the start, Roosevelt was

committed to making the government work for the people, and in many respects,

the people never needed government more. The post-Civil War industrial

revolution had generated enormous wealth and power for the men who controlled

the levers of business and capital. Regulating the great business trusts to

foster fair competition without socializing the free enterprise system would be

one of Roosevelt's primary concerns. The railroads, labor, and the processed

food industry all came under his scrutiny. Although the regulations he

implemented were modest by today's standards, collectively they were a

significant first step in an age before warning labels and consumer lawsuits.

Internationally, America was on the threshold of world leadership.

Acquisition of the Philippines and Guam after the recent war with Spain

expanded the nation's territorial borders almost to Asia. The Panama Canal

would only increase American trade and defense interests in the Far East, as

well as in Central and South America. In an age that saw the rise of oceanic

steamship travel, the country's sense of isolation was on the verge of

suddenly becoming as antiquated as yardarms and sails.

A conservative by nature, Roosevelt was progressive in the way he addressed

the nation's problems and modern in his view of the presidency. If the people

were to be served, according to him, then it was incumbent upon the President

to orchestrate the initiatives that would be to their benefit and the

nation's welfare. Not since Abraham Lincoln, and Andrew Jackson before him,

had a President exercised his executive powers as an equal branch of

government. If the Constitution did not specifically deny the President the

exercise of power, Roosevelt felt at liberty to do so. "Is there any law that

will prevent me from declaring Pelican Island a Federal Bird Reservation? . .

.Very well, then I so declare it!" By executive order in March 1903, he

established the first of fifty-one national bird sanctuaries. These and the

national parks and monuments he created are a part of his great legacy.

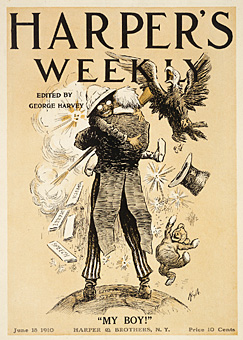

Theodore Roosevelt's dynamic view of the presidency infused vigor into a branch

of government that traditionally had been ceremonial and sedate. His famous

"Tennis Cabinet" was indicative of how he liked to work. Riding and hiking were

daily pastimes; one senator jested that anyone wishing to have influence with

the President would have to buy a horse. When the press could keep pace with

him, it reveled in his activities, making him the first celebrity of the

twentieth century. His spectacled image adorned countless magazine covers

before beauty, sex, and scandal became chic. This image of Roosevelt by Peter

Juley appeared on the cover of Harper's Weekly, July 2, 1904.

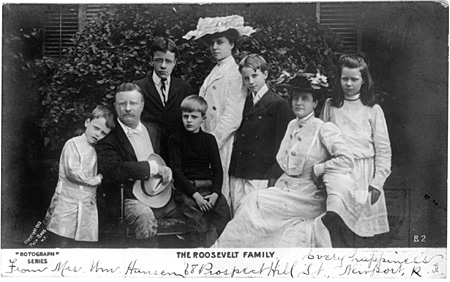

(Left to right):

Quentin (1897-1918), Theodore (1858-1919), Theodore Jr. (1887-1944),

Archibald (1894-1979),Alice Lee (1884-1980), Kermit (1889-1943), Edith Kermit

(1861-1948),

and Ethel Carow (1891-1977)

Like Roosevelt himself, the first family was young, energetic, and a novelty

in the White House. Public interest in them was spontaneous, as pictures of

Theodore, Edith, and their six children began appearing in newspapers and

magazines. For once in history, the executive mansion acquired aspects of a

normal American home, complete, with roller skates, bicycles, and tennis

racquets.

Theodore Roosevelt's eldest child, Alice Lee, was an impressionable

teenager when the family moved into the White House in 1901. High-spirited and

defiant by nature, she enjoyed pushing the limits of decorum, while competing

for her father's attention. Naturally she was a favorite of the press, which

called her Princess Alice. Stories about her antics, her favorite color, a

blue-gray dubbed "Alice blue," and her cast of acquaintances filled the

newspapers. She smoked in public, bet at the racetrack, and was caught speeding

in her red runabout by the Washington police. Photographs of her connote the

classic Gibson Girl and suggest an air of youthful haughtiness. In 1906, she

married Nicholas Longworth, a Republican congressman from Ohio. He was

fifteen years her senior, short and bald, and something of a bon vivant. Their

White House wedding was the most talked-about social event of the Roosevelt

years.

At the invitation of the first family, John Singer Sargent was a White House

guest for a week in the middle of February 1903, while he painted a portrait of

the President. For Sargent, the foremost Anglo-American portraitist of his era,

the experience was vexing in many respects. Particularly, Sargent found the

President's strong will daunting from the start. The choice of a suitable place

to paint, where the lighting was good, tried Roosevelt's patience. No room on

the first floor agreed with the artist. When they began climbing the staircase,

Roosevelt told Sargent he did not think the artist knew what he wanted. Sargent

replied that he did not think Roosevelt knew what was involved in posing for a

portrait. Roosevelt, who had just reached the landing, swung around, placing

his hand on the newel and said, "Don't I!" Sargent saw his opportunity and told

the President not to move; this would be the pose and the location for the

sittings. Still, over the next few days Sargent was frustrated by the

President's busy schedule, which limited their sessions to a half-hour after

lunch. Sargent would have liked to have had more time. Nevertheless, Roosevelt

considered the portrait a complete success. He liked it immensely, and

continued to favor it for the rest of his life. Commissioned by the federal

government, Sargent's Roosevelt is the official White House

portrait of the twenty-sixth President.

On an extended visit to the West in the spring of 1903, President Roosevelt

sought the company of naturalists John Burroughs and John Muir. With

Burroughs, Roosevelt camped in Yellowstone Park for two weeks, and with Muir he

explored the wonders of the Yosemite Valley and had his picture taken in front

of a giant sequoia tree in the Mariposa Grove. Roosevelt's visit was an

opportunity for Muir to be able to impress upon the President the need for

immediate preservation measures, especially for the giant forests. In 1908,

Roosevelt paid tribute to Muir by designating Muir Woods, a redwood forest

north of San Francisco, a national monument.

A hunting trip President Roosevelt made into the swamps of Mississippi in 1902

became legendary when he refused to shoot an exhausted black bear, which had

been run down by a pack of hounds and roped to a tree. Although the incident

was reported in the local press, Clifford K. Berryman, a staff artist for the

Washington Post, made it memorable on November 16 with a small front-page

cartoon titled "Drawing the Line in Mississippi." Roosevelt is shown holding a

rifle, but refusing to shoot the bedraggled bear. The bear, however, received

no executive clemency; Roosevelt ordered someone else to put the creature out

of its misery. Clifford Berryman elected to keep the bear alive in his

cartoons, and it evolved, ever more cuddly, as a companion to Roosevelt,

ultimately spawning the Teddy Bear craze.

The Restless Hunter , 1909 - 1919

Only once in American history had a President vacated the White House and

then returned to it again as President. This had been Grover Cleveland's

unique destiny in 1893. That this had occurred within recent memory, and to a

politician in whose footsteps Roosevelt had followed as governor of New York

and finally as President, must have given Roosevelt reason to pause as he

himself became a private citizen again in March 1909. He was only fifty years

old, the youngest man to leave the executive office. Cleveland had been just

eighteen months older when he temporarily yielded power to Benjamin Harrison

in 1889. For the record, Roosevelt claimed that he was through with politics.

This was the only thing he could have said as William Howard Taft, his

successor, waited in the wings. Theodore Roosevelt had enjoyed being

President as much as any person possibly could. Filling the post-White House

vacuum would require something big and grand, and with that in mind,

Roosevelt planned his immediate future. The prospect of a yearlong safari in

Africa brightened for him what otherwise would have been the dreary prospect

of retirement. It "will let me down to private life without that dull thud of

which we hear so much," he wrote.

Aided by several British experts, Roosevelt oversaw every preparation:

itinerary, gear and clothing, food and provisions, weapons, personnel, and

expenses. He had been an avid naturalist and hunter since the days of his

youth. Because he was genuinely interested in the African fauna, he arranged

for his safari to be as scientific as possible, and enticed the Smithsonian

Institution to join the expedition by offering to contribute extensively to

its fledgling collection of wildlife specimens. Roosevelt invited his son,

Kermit, along for companionship, if the lad would be willing to interrupt his

first year of studies at Harvard. Kermit needed no persuading.

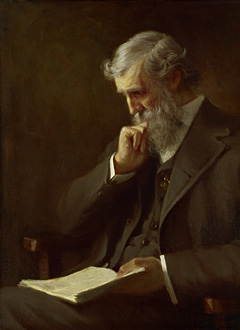

By President Roosevelt's last year in the White House, he had long grown

tired of requests to sit to photographers and portrait painters. Only as a

favor to an old friend from England, Arthur Lee, did he agree to sit for a

portrait by the accomplished Hungarian born artist, Philip A. de Laszlo. The

sittings took place in the spring of 1908, about which Roosevelt reported

enthusiastically to Lee. "I took a great fancy to Laszlo himself," he wrote,

"and it is the only picture which I really enjoyed having painted." Laszlo

encouraged the President to invite guests to the sittings to keep Roosevelt

entertained. "And if there weren't any visitors," said Roosevelt, "I would

get Mrs. Laszlo, who is a trump, to play the violin on the other side of the

screen." When the painting was finished, Roosevelt said that he liked it

"better than any other."

Ten years later, however, Roosevelt expressed a preference for Sargent's

portrait, done in 1903, which he thought had "a singular quality, a blend of

both the spiritual and the heroic." Still he thought that Mrs. Roosevelt

favored Laszlo's more relaxed image, a trademark of the artist's ingratiating

style.

Three weeks after Theodore Roosevelt left the White House in March 1909, he

embarked with his son, Kermit, upon an African safari, lasting nearly a year.

He had always wanted to hunt the big game of Africa, but he also wanted his

expedition to be as scientific as possible. With this in mind, he invited the

Smithsonian Institution to take part, and promised to give the Institution

significant animal trophies, representing dozens of new species for its

collections. Roosevelt himself made extensive scientific notes about his

African expedition. For instance, he was keenly interested in the flora of

Africa, and recorded the dietary habits of the animals he killed after

examining the contents of their stomachs.

While on safari, Roosevelt wrote extensively about his African adventure.

Scribner's magazine was paying him $50,000 for a series of articles, that

appeared in 1910 as a book, African Game Trails. This photograph

of Roosevelt with a bull elephant was used as an illustration.

In March 1910, Roosevelt ended his eleven month African safari and, reunited

with his wife, embarked on an extended tour of Europe. He accepted many

invitations from national sovereigns and gave much anticipated lectures at

the Sorbonne in Paris and at Oxford University in England. In Norway, he

delivered finally his formal acceptance speech for having won the Nobel Peace

Prize four years earlier. "I am received everywhere," he wrote, "with as much

wild enthusiasm as if I were on a Presidential tour at home."

This cover of Harper's Weekly, June 18, 1910, was one of numerous

graphic commentaries celebrating Roosevelt's return to the United States.

Supreme Court Justice David J. Brewer used to jest that William Howard Taft

was the politest man in Washington, because he was perfectly capable of giving

up his seat on a streetcar to three ladies. Taft's amicable disposition it was

said that his laugh was one of the "great American institutions" was the

foremost quality that won Roosevelt's admiration. "I think he has the most

lovable personality I have ever come in contact with," said Roosevelt. As

governor general of the Philippines and then as secretary of war, Taft proved

to be a troubleshooter in Roosevelt's cabinet. His longtime ambition had been

to someday sit with Justice Brewer on the bench of the Supreme Court. Taft

would ultimately succeed to the Court, but not before Roosevelt pegged him to

be his successor. "Taft will carry on the work substantially as I have carried

it on," predicted Roosevelt. "His policies, principles, purposes and ideals are

the same as mine." Yet when Taft later proved to be his own person, Roosevelt

was distraught. Taft failed to convey the spirit of progressivism to which

Roosevelt was ever leaning. "There is no use trying to be William Howard Taft

with Roosevelt's ways," he bemoaned, "our ways are different."

Coaxed by his political admirers, and personally dissatisfied with what he

considered to be President Taft's lack of leadership, Roosevelt announced early

in 1912 that he would run for a historic third presidential term, if the GOP

nomination were tendered to him. This was a monumental decision on his part,

one he made contrary to his own established beliefs in the tradition of party

loyalty, and without the full backing of party leaders. Roosevelt was counting

on winning the support of the people, and was successful in those states that

had direct primaries. But in June, at the Republican convention in Chicago, the

party machine wrested control of the proceedings and nominated President Taft

easily after the Roosevelt delegates had walked out. This was the start of the

Progressive Party, in which Roosevelt proudly accepted the nomination. The

press was especially happy to have him back in the running. From the moment he

declared, "My hat is in the ring," he became the most visible, if not viable,

candidate. Ultimately, Roosevelt would beat Taft in the election, but he would

lose to the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson. This cover of Judge

, August 6, 1910, raised "the question" from early on--"Can a champion come

back?"

Theodore Roosevelt once declared himself to be "as strong as a bull moose." The

appellation stuck and the moose became the popular symbol for the Progressive

Party under Roosevelt. This cartoon depicting the mascots of the major parties

appeared in Harper's Weekly, July 20, 1912, just before the "Bull

Moose" convention opened in Chicago.

Chronology of the Public Career of Theodore Roosevelt

1882-1884 - New York State Assemblyman

1889-1895 - United States Civil Service Commissioner

1895-1897 - New York City Police Commissioner

1897-1898 - Assistant Secretary of the Navy

1898 - Rough Rider

1899-1900 - Governor of New York

1901- Vice President of the United States

1901-1909 - President of the United States

Source

1. www.yahoo.com

2. http://www.npg.si.edu/exh/roosevelt/index.htm |